Identity Hurts

Scroll down to start.

L iane Lim* dabbles with plastic surgery procedures as casually as people change their style.

When she was younger, Liane’s grandmother would tell her her nose stood out from her otherwise “very nice features”. People pinched her chubby cheeks, and, on holiday, foreigners commented on her small eyes.

“What people value are big eyes, double eyelids; a nice balanced facial structure,” said Liane, now 23. “Then you feel like there’s something wrong with you and you need to change.”

So change she did. In May 2016, she dipped her toes in the waters of cosmetic surgery for the first time, paying $800 for 1ml of nose fillers, to raise her nose bridge temporarily.

In June, she flew to Bangkok for two cheek-reduction procedures.

A month later, Phuket – for three different eyelid surgeries, and a chin liposuction.

At seven procedures in just three months, the final-year student from Nanyang Technological University is aware that, to some, her experiences might appear as addiction to plastic surgery. But Liane is adamant she knows where to draw the line, especially now she’s corrected the features that made her feel insecure in the past.

The procedures are just like accessorising, she says.

“It’s like, let’s say, you can decorate your room – why wouldn’t you decorate it the way you want, right?” she adds earnestly. “So it’s the same thing for your body, except that you have to work with what you already have.”

While many would react with disbelief, more young people are sharing this sentiment today.

Bradley Tan, 29, and Ian Low, 33, both millennials and heavily inked tattoo artists, deadpanned that collecting tattoos is the same as collecting shoes or hoarding makeup.

“Right now I have more free space than I have tattooed,” said Bradley, who owns Oracle Tattoo studio. “It hurts, but I do intend to be completely covered eventually.”

Not a numbers game: When asked how many tattoos they have, tattoo artists Bradley Tan (left) and Ian Low (right) shared the same sentiment: "Usually when it comes to our stage it’s not about how many you have already – it’s which area of skin you haven’t tattooed yet."

Over in the gym, 23-year-old Ian Thaver maintains his massive frame with strenuous weight training five times a week, because he loves watching his body build muscle. The sculpted second-year student at Curtin University receives stares everyday for his larger-than-life shape, but takes pride in knowing that he created it himself.

Experimenting with clothing, hair and makeup have always formed the basis of expressing individuality. But for this group of 18- to 35-year-olds, identity means carving their appearance with permanence, where temporary material accessories no longer suffice.

The emphasis on appearances is universal – clinical expert on body dysmorphic disorder Dr. Oliver Suendermann, 37, said everyone exists on a spectrum of body dissatisfaction. Rather, it’s when social media comes into play that youths start looking beyond to add on to their physical appearance.

The clinical psychologist at the National University of Singapore called social media problematic for promoting image-crafting, a term to describe carefully constructing one’s social media content or profiles to control how others perceive their life. “So there’s a lot more comparing."

Sociologist Samuel Han, 33, thinks the desire for permanence, then, is just a result of there being more outlets available for self-expression in today’s society – be it plastic surgery, tattooing or bodybuilding. “People are making use of those new avenues,” said the assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University.

“It’s that kind of flexibility that humans have, in terms of crafting our identities, that allows for something like the thought of even changing ourselves.”

Perhaps it has to do with living in a time of extremes, where dichotomising phrases like “ride or die” punctuate daily vernacular, and the sociocultural environment is messy with polarising opinions. But as measures to carve an identity grow more extreme, it starts to become clear that millennials truly intend to go big or go home.

You have to do it for yourself.

Liane Lim

Push It: Expect a lot of heavy lifting at Radiance PhysioFit along Shenton Way. Spurred on by a prominent selfie culture and "clean" eating movement, many millennials are choosing to spend their free time in the gym.

Needle Culture

When millennials embrace change, they embrace the pain that comes with it. On the rise in Singapore are three industries that are a lot less pleasant than simply slathering on makeup.

While there are no exact counts of plastic surgery procedures, tattoo parlours, and bodybuilding practitioners, stakeholders in all three fields point to a marked increase in professionals catering to a corresponding demand.

Tattoo parlours, once limited to an easy 30 up until the 90s, have erupted into “a few hundred” islandwide, according to tattoo artist Sumithra Debi, 36, who is the third generation of tattoo artists in her familyHer late grandfather, Indra Bahadur, better known as Johnny Two Thumbs, popularised the local tattoo trade in the 50s and is regarded as the scene’s founding father..

In the fitness industry, too, gym-going culture is booming. The central business district alone has 17 gyms within a 3km radius of Raffles Place, catering to the nine-to-five working folk. US-based chain Anytime Fitness started with one outlet in Woodlands in 2013, and now operates 26 more; while locals like homegrown fitness company Gymm Boxx are also muscling in for a piece of the action, running six outlets in residential areas.

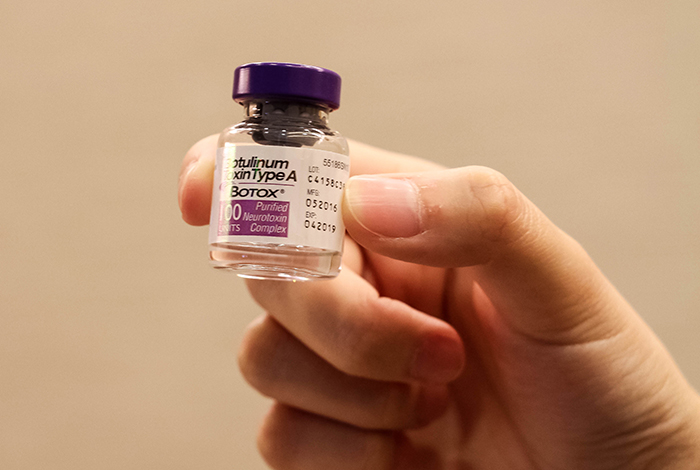

Money matters: In Singapore, a cosmetic procedure can range from $600 for a shot of Botox to $12,000 for a rhinoplasty. A tattoo costs anywhere from $50 for a small design to a few thousand for a full back piece. And gym membership fees are hefty – Gymm Boxx rates go from $50 to $80 per month, depending on the subscription package.

And over in the plastic surgery world, doctors have noticed a difference in their clientele – no longer are they just middle-aged women looking for a touch of rejuvenation; the demographic has expanded to include more young adults going under the knife.

If it seems extreme, it is – and that’s the point. The trend towards aesthetic self-improvement means no holding back, whether it’s having needles poked around or parting with hard-earned money. In fact, the youth interviewed expressed no qualms about paying through the nose to achieve what was important to them – in true fashion of the Affluent Millennial.

In a 2015 study conducted by business social network LinkedIn, Affluent Millennials in Singapore were defined as those who have $150,000 in investible assets, excluding real estate, amongst 1.2 million millennials in Singapore. The study found that these young adults are not worried about splashing out now, due to their optimism about being able to deal with future financial obligations. Nearly 80 per cent believe that any sacrifice they make now will pay off in the future.

Liane, who saved up for three years teaching yoga part-time, paid for all her procedures herself, and feels more secure in knowing that her decisions were made without financial help from her parents.

Sharing plans for her next operation – a rhinoplasty to make the changes her first nose fillers achieved, permanent – she adds: “You have to do it for yourself.”

You're marking yourself as different and very individual – and that's not something that fits in comfortably in most Asian societies.

Neil Gains

Stigma: The struggle is real

I

n the face of a growing inclination towards improving appearances, general support, however, is lacking. Youths and professionals alike acknowledge that the growth is against a backdrop of stigma that even today is hard to shake.

Individually, each of the three industries has their own disgraces to deal with. With the line separating reconstructive and cosmetic surgery so finely drawn, many still take issue with surgery that doesn’t address medical needs. The Ministry of Health regulates that no doctor or surgeon can use the term ‘aesthetic’ in their title, so as not to promote a disposable attitude towards surgery.

Bodybuilding, greatly supported by Sport Singapore in the 90s, now struggles to make its comeback in the wake of steroid abuse scandals in 2012.

And from its controversial association with fringe communities like sailors in the 50s, to today, the tattoo industry has never once been regulated – because, Professor Han speculates, “that forces the government to have a position on tattoos”.

The sting of stigma: At Oracle Tattoo, Bradley Tan says stigma is alive and well – especially in Singapore. "We’re a diverse country with a lot of different cultures, but then again we’re very Asian as well. Some of the older generation still look at you a bit differently."

If the compulsion to sweep things under the rug seems familiar, it may be because it mirrors the general attitude from a population still unwilling to fully embrace taboos and extremities; unfortunately, these people make up the majority.

But market analyst Neil Gains, who has a doctorate in psychology and social science, speculates that the resistance towards such extreme modifications lies with how humans, and especially Asians, reject the idea of permanent changes to the body. Makeup for example, he said, is more accepted because it washes off at the end of the day.

“In Bahasa the local word for cosmetics is dan dan, which means ‘and and’, or ‘add add’; like stuff you add to your face,” said Gains, 52, who has done cultural analysis on the local beauty markets in Indonesia, China and Singapore for 16 years. “It’s a temporary ephemeral thing, and it’s playful, experimental – the underlying person doesn’t change.”

“If you make change to your body that other people notice and which makes you look different from everyone else, you’re marking yourself as different and very individual,” he added.

“It’s a big statement about who you are, and that’s not something that fits in comfortably in most Asian societies, broadly.”

Ink

Tattoos in Singapore have always been contentious. A prominent history of gang culture in the early 80s, where gang members were often marked with tattoos to denote membership and loyalty, has left many from the older generation still hostile towards the idea of ink for art.

Gregory Chan, 54, has had to watch his three sons decorate their bodies with permanent ink. He’s since come to accept it, but when his eldest, Bryan, first came home with a large cross on his upper right arm – a 21st birthday present to himself – in 2006, Mr. Chan wasn’t too pleased.

“I told him in the streets he would pass off as any gangster,” said Mr. Chan, who is a banker. “I’m a corporate guy; if he had asked me before getting the tattoo my answer would be no, because it gives a wrong impression.”

Bryan, now 31, runs a family tuition centre, but with a full sleeve of black ink tattooed down to his left hand, he cuts a surprising figure as a tutor.

First ink-pressions: Business is brisk now, but 10 years ago when he was starting out in tuition, Bryan Chan would wait patiently as his mother introduced him as a tutor to her friends, knowing, in short-sleeved shirts, that he wouldn’t receive their business.

From his tuition centre at Beauty World Centre, Bryan remarks that the air around tattoos has changed since then, but that he still takes precautions around more conservative parents.

“I have students who know I’m tattooed; and their parents know. But for some students, some parents, you know they’re old-school – so I cover up. You can tell after a while,” he adds.

Right on cue, a young girl in the Singapore Chinese Girls School uniform walks through the door, and Bryan deftly throws his jacket over his exposed arm.

It’s more out of courtesy for that generation, the educator, who has twin nine-year-old sons, insists. When the family goes out for dinner with Bryan’s maternal grandfather, all three brothers wear long golfing sleeves or jackets – even in the sweltering heat of eating zi char.

“He’s an old-school guy. When he watches his Chinese or Korean dramas and sees characters with (tattoo) sleeves, he will start shouting vulgarities, and ‘what an idiot!’” says Bryan.

“But just let him be lah, old man."

Muscle

When it comes to bodybuilding, the reason behind the furrowed brows and pointed whispers is less straightforward. According to experts, the stigma has to do with a human aversion to unnaturalness.

For bodybuilders, the mantra “the bigger the better” is cliched but true. And Singapore doesn’t seem quite ready to accept that kind of size at face value, according to Dr. Yang Yifan, 42.

The assistant professor, who teaches sports science and sports nutrition in the National Institute of Education, said social norms play a bigger role here, where the history of the sport does not extend as far back as in the US.

“In terms of aesthetics, because it’s a little bit more extreme, sometimes it’s controversial where for average people like us, it may be a bit harder to accept, or to maybe imagine that it’s possible,” she said, adding that prejudices favour female bodybuilders even less.

In addition, the common association with steroids, for obvious reasons has, coloured the act of building muscle with controversy.

“I’m not saying that everybody does it, but because it’s quite rampant, it creates a problem – that bad image and the association with drugs,” Dr. Yang said.

“A lot of times people will think ‘is this natural or is it artificial?’, so it’s controversial in that sense.”

Benjamin Broughton, 22, has been training as an up-and-coming amateur bodybuilder for four years now, but says he’s been accused of steroid abuse multiple times.

“When I was younger I had super bad acne and everyone said ‘oh you’re on steroids’, and I was just like, ‘I have acne’,” he said, shrugging.

Man in the mirror: Benjamin Broughton, 22, poses for his weekly photo-taking sessions to check on his muscle-building progress.

His mother Celeste Png, though supportive, had her doubts about the sport in the beginning. "I wasn't comfortable with people looking at my son's body," she said. "And I still get offended when people see a photo of him and say they're drooling over him."

Silicone

Five out of eight interviewed about their plastic surgery asked to remain anonymous – not for shame, but because they feared the association with vanity or climbing career ladders that others might tend to assume.

“There is stigma still,” Liane admitted. “I’m afraid people will associate doing cosmetic surgery with being vain and superficial, which I know I’m not. Sure, maybe 5 per cent of me is vain and superficial, but it’s not 100 per cent of me.”

Having cosmetic surgery has also been commonly viewed as means to excel in the workplace, a perception supported by the beauty literature. “Beauty premiums” reward more attractive people with higher chances of employment, better pay and all-round better treatment, according to post-doctoral research fellow Natalie Truong, 30.

“Some people say ‘no, you just have to be good at your job to get a higher pay; beautiful or not, it doesn’t matter’,” said Truong, who is conducting a study at the Institute on Asian Consumer Insight on how people perceive beauty.

“That’s not true – at least not according to research. And figures never lie.”

Hence the negative feedback towards anything that might give someone else a leg up the social and career ladder. In fact, presumptuous gossip about ‘ulterior motives’ is a possibility student Fiona Tan*, 24, has already considered.

The final-year student, whose freshly cut double eyelids coincided unfortunately with the launch of her new startup, expressed concerns about being perceived as using looks to get ahead. But she proceeded anyway, after years of fussing with eyelid tape, because “you don’t want to go against the system”.

Aftercare: For the week after her double eyelid surgery, Fiona Tan cleaned her healing eyelids with cotton pads soaked in a sterile solution. To keep water from going into her eyes, she stayed away from makeup, and had her hair washed for her at salons.

“Society treats good-looking people better – and I don’t want to be given special treatment for being more good-looking; but I don’t want people to assume that I’m not skilled just because of my looks,” she said.

“It’s more like surviving, than trying to thrive, based on looks.”

The new normal

But the sting of disapproval from the more conservative is losing its significance. As more youths find comfort in the fact that numbers in their favour are growing, it seems going to extremes is becoming increasingly normalised.

Back in the Chan household, 26-year-old Timothy and his father have moved on to discussing cosmetic surgery among youths. The 58-year-old banker stares incredulously as his second son recounts how a schoolmate booked her rhinoplasty procedure at 18, flying abroad for it right after her International Baccalaureate exams.

“Is it normal to do a nose job so young?” he asks.

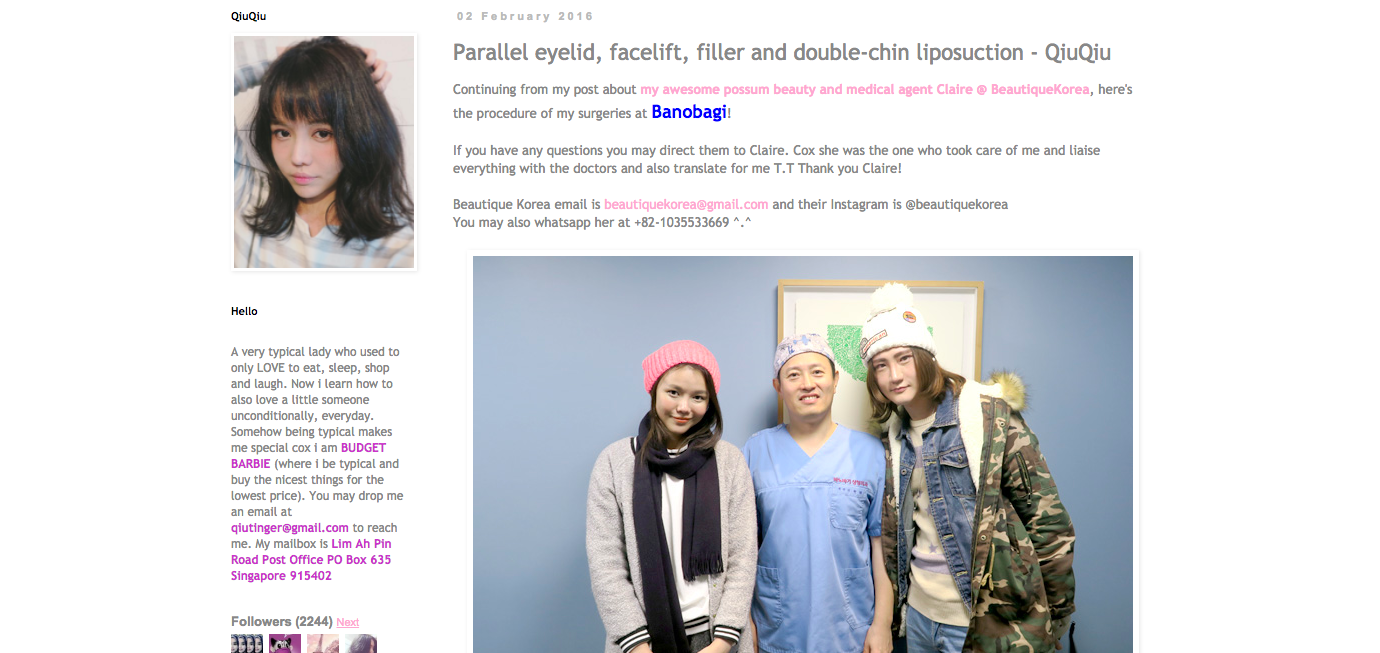

It may largely be sponsored content, but reviews from trusted local bloggers like Wendy Cheng, also known as Xiaxue, and Bong Qiuting serve as both useful research material and moral support for Singaporean youths. PHOTOS: WENDY CHENG, BONG QIUTING

Timothy side-eyes his father and replies: “I don’t know lah; nowadays everything is about the new normal.”

As previously stigmatised measures gain mainstream popularity, so do youths feel increasingly justified to do what “everyone else is doing”. Both Liane and Fiona agreed that being able to see more girls post about their cosmetic surgery experiences on blogs and social media helped open them to the idea, as well as reassure them that they weren’t alone.

“Cosmetic surgery is getting more and more normal, and people use it to feel more confident about themselves,” said Liane, who pored over reviews from Singapore Expat Forum and local bloggers before making her decision.

And on responding to detractors, she added: “It’s not about impressing others as much as feeling confident in your own skin.”

There’s a certain rallying collectivism in feeling confident in tattooed skin as well. For anyone with a tattoo, the sudden ability to identify with a new in-group of fellow inked bodies should come as no surprise. At Oracle Tattoo, Ian Low likes to welcome first-timers to the dark side after they’ve abandoned their “clean” skin.

“Sure, we’re still a minority group, and we stand out in a crowd, but we’re fitting in with the minority,” he added. “I like to tell them, ‘okay, you’re one of us now.’”

We stand out in a crowd, but we’re fitting in with the minority.

Ian Low

Benedict Choo certainly agrees. The 19-year-old Singapore Polytechnic student says that since getting his tattoos, people identify him as the “ang kong siao” (person with many tattoos). But he doesn’t mind – in fact, he enjoys the new interactions with fellow tattoos enthusiasts his ink has brought him.

Twice on the train, he had conversations with complete strangers, initiated simply out of mutual interest in each other’s tattoos. “It’s like a common platform for us; it’s a culture already. We went through similar things so we have something in common to talk about,” he said.

As for Ian Thaver and Benjamin, negative feedback doesn’t bother them – especially when they’re surrounded by 20 other people furiously pumping iron.

Benjamin, who started hitting the gym seriously in 2012, sees himself as being ahead of the curve, but observed that more youths are gaining interest in working out.

“I think it’s got a lot to do with what they want to be identified with,” he said. “It’s a big deal, which is why people always make it a point when they go to the gym to let others know they’re going to the gym.”

Sorry not sorry

So does the fuzzy feeling of belonging take away from the journey towards carving identity and individuality? Not at all, say youths, because method and motivation are separate issues.

All mine: Mandalas may turn out to be a passing fad, but that hasn't stopped Benedict from adding them to his one-of-a-kind tattoo sleeve.

A cosmetic procedure isolates and improves a specific feature unique to the person; every tattoo comes with its own special meaning for its wearer; and sculpting the body works on maximising the genetic potential of individual bodies.

“If I have a full tattoo sleeve and another guy has a full sleeve, what would be different is that I will feel like my sleeve is nicer because it was my ideas,” explained Benedict, said sleeve showing from below his white T-shirt.

“It means that I have full control of my life; that I can assert my full will on my own body. Because it’s mine.”

And so it goes – whether it’s in controlling how they want to look like the best version of themselves, or taking charge of the bodies they were given, the point lies not in what was done, but why; and no two reasons are alike.

So until criticism against being your own person can one day be justified, millennials will continue to do as they please. Mr. Chan fondly recalls a family outing to Changi Village three years back, where he noticed a couple in their 50s from the next table staring oddly at them – man, wife and three tattooed sons eating nasi lemak. He walked over, passed them his phone, and asked them to help take a family photo.

“It’s a different world today,” Mr. Chan muses, an amused smile creeping onto his face. “Live and let live.”

Indeed. And as the teens tell each other, through supportive texts, tweets and DMs, these days: You do you.

*Names have been changed.